“Years ago we came to the conclusion that global warming was a problem, it was an urgent problem and the need for action is now. The problem appears to be worse and more imminent today, and the need to take action sooner and take more significant action is greater than ever before” — PG&E Chairman and CEO Peter Darbee

“Years ago we came to the conclusion that global warming was a problem, it was an urgent problem and the need for action is now. The problem appears to be worse and more imminent today, and the need to take action sooner and take more significant action is greater than ever before” — PG&E Chairman and CEO Peter Darbee

The head of one of the nation’s largest utilities seemed to be channeling Al Gore on Tuesday when he met with a half-dozen environmental business writers, including Green Wombat, in the PG&E (PCG) boardroom in downtown San Francisco. While a lot of top executives talk green these days, for Darbee green has become the business model, one that represents the future of the utility industry in a carbon-constrained age.

As Katherine Ellison wrote in a feature story on PG&E that appeared in the final issue of Business 2.0 magazine last September, California’s large utilities — including Southern California Edison (EIX) and San Diego Gas & Electric (SRE) — are uniquely positioned to make the transition to renewable energy and profit from green power.

First of all, they have no choice. State regulators have mandated that California’s investor-owned utilities obtain 20 percent of their electricity from renewable sources by 2010 with a 33 percent target by 2020. Regulators have also prohibited the utilities from signing long-term contracts for dirty power – i.e. with the out-of-state coal-fired plants that currently supply 20 percent of California’s electricity. Second, PG&E and other California utilities profit when they sells less energy and thus emit fewer greenhouse gases. That’s because California regulators “decouple” utility profits from sales, setting their rate of return based on things like how well they encourage energy efficiency or promote green power.

Still, few utility CEOs have made green a corporate crusade like Darbee has since taking the top job in 2005. And the idea of a staid regulated monopoly embracing technological change and collaborating with the likes of Google (GOOG) and electric car company Tesla Motors on green tech initiatives still seems strange, if not slightly suspicious, to some Northern Californians, especially in left-leaning San Francisco where PG&E-bashing is local sport.

Still, few utility CEOs have made green a corporate crusade like Darbee has since taking the top job in 2005. And the idea of a staid regulated monopoly embracing technological change and collaborating with the likes of Google (GOOG) and electric car company Tesla Motors on green tech initiatives still seems strange, if not slightly suspicious, to some Northern Californians, especially in left-leaning San Francisco where PG&E-bashing is local sport.

In a wide-ranging conversation, Darbee, 54, sketched sketched a future where being a successful utility is less about building big centralized power plants that sit idle until demand spikes and more about data management – tapping diverse sources of energy — from solar, wind and waves to electric cars — and balancing supply and demand through a smart grid that monitors everything from your home appliances to where you plugged in your car. “I love change, I love innovation,” says Darbee, who came to PG&E after a career in telecommunications and investment banking.

Renewable energy

“On renewable energy what we’ve seen is the market is thin,” says Darbee. “Demand just from ourselves is greater than supply in terms of reliable, well-funded companies that can provide the service.”

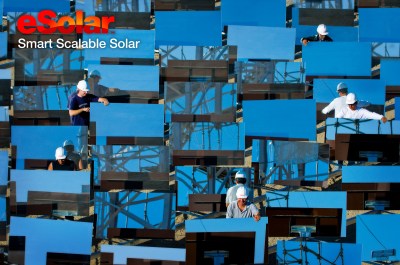

PG&E so far has signed power purchase agreements with three solar startups — Ausra, BrightSource Energy and Solel — for up to 1.6 gigawatts of electricity to be produced by massive solar power plants. Each company is deploying a different solar thermal technology and uncertainty over whether the billion-dollar solar power stations will ultimately be built has prompted PG&E to consider jumping into the Big Solar game itself.

“We’re looking hard at the question of whether we can get into the business ourselves in order to do solar and other forms of renewables on a larger scale,” Darbee says. “Let’s take some of the work that’s been done around solar thermal and see if we can partner with one of the vendors and own larger solar installations on a farm rather than on a rooftop.”

“I like the idea of bringing the balance sheet of a utility, $35 billion in assets, to bear on this problem,” he adds.

It’s an approach taken by the renewable energy arm of Florida-based utility FPL (FPL), which has applied to build a 250-megawatt solar power plant on the edge of the Mojave Desert in California.

For now, PG&E is placing its biggest green bets on solar and wind. The utility has also signed a 2-megawatt deal with Finavera Renewables for a pilot wave energy project off the Northern California coast. Given the power unleashed by the ocean 24/7, wave energy holds great promise, Darbee noted, but the technology is in its infancy. “How does this technology hold up against the tremendous power of the of the Pacific Ocean?”

Electric cars

Darbee is an auto enthusiast and is especially enthusiastic about electric vehicles and their potential to change the business models of both the utility and car industries. (At Fortune’s recent Brainstorm Green conference, Darbee took Think Global’s all-electric Think City coupe for a spin and participated in panels on solar energy and the electric car.)

California utilities look at electric cars and plug-in hybrids as mobile generators whose batteries can be tapped to supply electricity during peak demand to avoid firing up expensive and carbon-spewing power plants. If thousands of electric cars are charged at night they also offer a possible solution to the conundrum of wind power in California, where the breeze blows most strongly in the late evenings when electricity demand falls, leaving electrons twisting in the wind as it were.

“If these cars are plugged in we would be able to shift the load from wind at night to using wind energy during the day through batteries in the car,” Darbee says.

The car owner, in other words, uses wind power to “fill up” at night and then plugs back into the grid during the day at work so PG&E can tap the battery when temperatures rise and everyone cranks up their air conditioners.

Darbee envisions an electricity auction market emerging when demand spikes. “You might plug your car in and say, ‘I’m available and I’m watching the market and you bid me on the spot-market and I’ll punch in I’m ready to sell at 17 cents a kilowatt-hour,” he says. “PG&E would take all the information into its computers and then as temperatures come up there would be a type of Dutch auction and we start to draw upon the power that is most economical.”

That presents a tremendous data management challenge, of course, as every car would need a unique ID so it can be tracked and the driver appropriately charged or credited wherever the vehicle is plugged in. Which is one reason PG&E is working with Google on vehicle-to-grid technology.

“One of the beneficiaries of really having substantial numbers of plug-in hybrid cars is that the cost for electric utility users could go down,” says Darbee. “We have a lot of plants out there standing by for much of the year, sort of like the Maytag repairman, waiting to be called on for those super peak days. And so it’s a large investment of fixed capital not being utilized.” In other words, more electric and plug-in cars on the road mean fewer fossil-fuel peaking power plants would need to be built. (And to answer a question that always comes up, studies show that California currently has electric generating capacity to charge millions of electric cars.)

Nuclear power

Nuclear power is one of the hotter hot-button issues in the global warming debate. Left for dead following the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl disasters, the nuclear power industry got a new lease on life as proponents pushed its ability to produce huge amounts of carbon-free electricity.

“The most pressing problem that we have in the United States and across the globe is global warming and I think for the United States as a whole, nuclear needs to be on the table to be evaluated,” says Darbee.

That’s unlikely to happen, however in California. The state in the late 1970s banned new nuclear power plant construction until a solution to the disposal of radioactive waste is found. PG&E operates the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant, a project that was mired in controversy for years in the ’70s as the anti-nuke movement protested its location near several earthquake faults.

“It’s a treasure for the state of California – It’s producing electricity at about 4 cents a kilowatt hour,” Darbee says of Diablo Canyon. “I have concerns about the lack of consensus in California around nuclear and therefore even if the California Energy Commission said, `Okay, we feel nuclear should play a role,’ I’m not sure we ought to move ahead. I’d rather push on energy efficiency and renewables in California.”

The utility industry

No surprise that Darbee’s peers among coal-dependent utilities haven’t quite embraced the green way. “I spent Saturday in Chicago meeting with utility executives from around the country and we’re trying to see if we can come to consensus on this very issue,” he says diplomatically. “There’s a genuine concern on the part of the industry about this issue but there are undoubtedly different views about how to proceed and what time frames to proceed on.”

For Darbee one of the keys to reducing utility carbon emissions is not so much green technology as green policy that replicates the California approach of decoupling utility profits from sales. “If you’re a utility CEO you’ve got to deliver earnings per share and you’ve got to grow them,” he says. “But if selling less energy is contradictory to that you’re not going to get a lot of performance on energy efficiency out of utilities.”

“This is a war,” Darbee adds, “In fact, some people describe [global warming] as the greatest challenge mankind has ever faced — therefore what we ought to do is look at what are the most cost-effective solutions.”

Read Full Post »