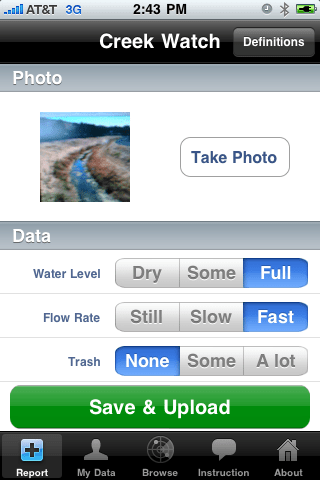

photo: Todd Woody

I wrote this story for Grist, where it first appeared.

If you want a birds-eye view of the future of power, scramble up to the roof of a 562,089-square-foot warehouse in Ontario, a city that sits in the smoggy heart of Southern California’s Inland Empire east of Los Angeles.

On a roof the size of several football fields, workers are busy installing 11,591 solar panels that will generate 2.55 megawatts of electricity. Across the street is another massive warehouse blanketed in photovoltaic panels. Beyond that lie two more warehouses with solar arrays under construction.

Warehouses themselves use relatively little electricity, so owners lease their roofs to utility Southern California Edison, which own the solar arrays and feeds the power they produce into the grid. Over the next five years, the utility will install 250 megawatts worth of photovoltaic panels on big commercial rooftops and buy an additional 250 megawatts from solar developers that will build and operate warehouse arrays. At peak output, those solar arrays will generate as much electricity as a mid-sized fossil-fuel power plant.

“In the Inland Empire you’ve got big buildings and good sun,” Rudy Perez, manager of the utility’s solar rooftop program, said as we stood on the top of the warehouse where solar panels covered the roof as far as the eye could see.

He noted that the number of applications from solar developers to connect rooftop photovoltaic projects to the grid has tripled in the past six months alone.

“It’s one thing when you have one building in an area with a big solar array, another when you have five,” said Perez. “As you get into the higher and higher numbers, that’s where you really need smart grid technology.”

That’s because the rise of renewable energy and electric cars will vastly complicate how the power grid operates.

“We could literally have more change in the system in the next 10 years than we’ve had in the last 100 years,” Theodore F. Craver, Jr., chief executive of the utility’s parent company, Edison International, said in an interview after meeting with executives from French utility giant EDF. The French had come to Los Angeles to learn about Southern California Edison’s smart grid efforts.

In the current, mostly analog grid, the distribution of electricity is fairly straightforward. A utility or another company builds a fossil-fuel-powered plant and flips the switch. For the next 30 years or more, electricity flows into high-voltage transmission lines hour after hour, day after day.

The transmission lines carry the electricity to a distribution system where transformers “step down” the power to a lower voltage and then send it to homes and businesses. And though technological improvements have been made over the decades to the grid, it remains essentially a one-way system. And while storms and accidents can bring down power lines and blackouts can occur when demand soars on a hot day and electricity generation can’t keep up, power flows 24/7 from a natural gas or coal-fired plant.

Now consider the challenges posed by intermittent sources of electricity like solar and wind, not to mention the prospect of thousands of cars plugging into the grid at once to recharge their batteries.

“A rolling cloud can cut electrical output by 80 percent in a just few seconds,” says Perez. “That’s one reason why we have to be smart about where we put [solar].”

And why it’s necessary to build a digitalized grid that deploys software, sensors, and other hardware to monitor and manage electricity distribution and troubleshoot problems.

Instead of relying on dozens of big power plants, the smart grid of the future will increasingly tap thousands or millions of individual rooftop power plants and wind turbines. It will need to collect information about their electricity output and balance the flow of electricity throughout the grid — to ensure that a neighborhood doesn’t go dark because a large cloud is hovering over the solar array atop the local Costco.

“As we start to replace more of the generation with different technologies, we are altering the physics of the system,” said Pedro Pizarro, Southern California Edison’s executive vice president of power operations.

This drizzly October morning is a case in point. A ceiling of gray clouds hangs over the four Ontario warehouses that altogether would be generating some 7.59 megawatts if the sun were shining at peak intensity. So the smart grid also needs to be able to forecast the weather and know, say, that for the next few days electricity production is going to fall in one area while it might rise another, sun-splashed one.

“There’s new technologies that allow for much precise control of the grid,” Perez said. “One of the concerns would be that the intermittency of one of these buildings causes problem for our customers.”

Down the coast at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), researchers have built what looks like a mirrored hemispherical bowl that scans the skies and snaps two photos a minute to predict when clouds will form over the campus’ one-megawatt worth of solar panels that are installed at seven locations.

“We do a 3-D characterization of all clouds on the horizon every 30 seconds,” Byron Washom, director of strategic energy initiatives at UCSD, said at a solar conference in October. “And then in the next second we note its vector, its speed, its height, its opacity and we characterize it.”

“So we actually begin to forecast what type of cloud is going to intersect where the sun is,” added Washom. “We know where it is at all times in the sky [in relation to] each individual panel on campus.”

He said the scientists’ goal is to be able to use the machines, which cost $12,000 apiece and have a range of one kilometer (0.62 miles), to do hourly forecasts with 90 percent accuracy.

“So a capital investment of less than $1 million could bring this to the Southern California rooftop market if we crack the science,” said Washom, referring to the concentration of warehouses in places such as Ontario.

Another smart grid strategy is to store energy generated by solar arrays in batteries and feed power to the grid when renewable energy production falls or demand spikes.

Washom showed a picture of a device that looks like the back end of a DVD player. The Sanyo lithium ion battery can store 1.5-kilowatt hours of electricity. UCSD plans to stack them like servers in a data center so it can store 1.5 megawatts of electricity produced by campus solar arrays.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, SolarCity, a solar panel installer, and electric carmaker Tesla Motors have received a $1.8 million state grant for a pilot project that will put lithium ion car batteries in half a dozen homes with rooftop solar arrays.

The Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD), meanwhile, plans to install lithium ion batteries in 15 residences as part of its smart solar homes program. The utility will also put two 500-kilowatt batteries near substations to test energy storage on a larger scale.

Such systems are expensive but if the price eventually falls, utilities would be able to use them to release power to the grid when, say, a one of Washom’s cloud-forecasting devices predicts electricity production will fall off. (SMUD also will deploy 70 solar stations to help it forecast weather conditions that could affect electricity production, according to Mark Rawson, the utility’s project manager for advanced, renewable and distributed generation.)

So will the smart grid and increasing production of rooftop solar and other renewable energy spell the end of big centralized power stations and the multibillion-dollar transmission infrastructure? Will the future bring some sort of Ecotopian nirvana where power is put in the hands of the people (or at least on their rooftops)?

Not anytime soon, according to Pizarro of Southern California Edison, barring technological breakthroughs that dramatically reduce the cost of photovoltaic power.

“Right now solar is increasing but it’s not overwhelming the system,” says Pizarro, noting that rooftop photovoltaics remain a tiny percentage of the overall power supply even in places like California, where utilities must obtain a third of their electricity from renewable sources by 2020.

Still, renewable energy “has the potential to reduce the generation from central stations,” Pizarro said. “It’s a question of how much and how soon.”

The other wild card is the price of oil and natural gas, notes Craver, Edison’s chief executive. When the cost of natural gas — the dominant energy source in California — rises, renewable energy becomes more attractive. When natural gas prices plunge, as they have over the past couple of years, installing solar becomes far more expensive in relative terms.

At last month’s solar conference, SMUD’s Rawson said his utility currently relies on photovoltaics, or PV, for less than one percent of its electricity generation. But that will likely change dramatically in the years ahead, he says, as the smart grid evolves to handle the widespread distribution of solar power.

“We’re trying to change PV from something that is tolerated by the utility to something that is controlled by the utility,” he said.