For longtime Australian Greenpeace activist Danny Kennedy, one of the environmental group’s more memorable moves was when the Sydney crew climbed the roof of the prime minister’s home and installed solar panels to protest the government’s preference for Big Coal over renewable energy. (Note: Do not try this on the White House.)

For longtime Australian Greenpeace activist Danny Kennedy, one of the environmental group’s more memorable moves was when the Sydney crew climbed the roof of the prime minister’s home and installed solar panels to protest the government’s preference for Big Coal over renewable energy. (Note: Do not try this on the White House.)

These days, there’s a new, greener PM in power and Kennedy is in California, running a solar startup that aims to minimize the time spent on rooftops by doing for the solar business what Dell did for personal computers: Digitizing the entire enterprise to cut costs and create a mass market.

Putting photovoltaic panels on residential rooftops remains largely a labor-intensive cottage business, often involving multiple visits to a client’s home to make the sales pitch, measure the roof, and design a custom system. Sungevity, which officially launches Tuesday on Earth Day, takes all that online.

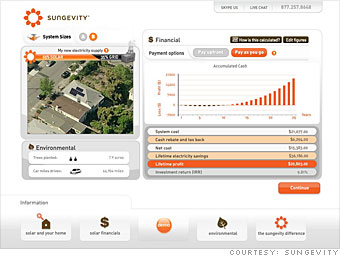

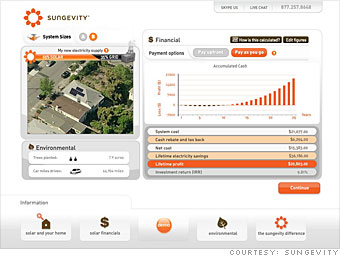

Enter your address on its website, and satellite-imaging software zooms in on your home, and Sungevity’s proprietary algorithm calculates the roof’s dimensions — the pitch and azimuth — selects appropriately sized solar arrays, and shows what they will look like installed — while computing your return on investment. Once the order is placed, one of five off-the-shelf prepackaged solar arrays is shipped to the customer’s door, and an installation crew is dispatched. A database tracks local building and permit requirements, sending the necessary forms to the homeowner for their signature while beaming local regulations governing solar arrays to the installation crew.

“This changes the game,” says Kennedy, 37, who co-founded Sungevity last year after leaving Greenpeace and relocating from Sydney to Berkeley. (Full disclosure: Kennedy’s kids and Green Wombat’s son attend the same elementary school.)

Kennedy and his partners have raised $2.7 million from investors that include German solar giant Solon and actress Cate Blanchett. “Our technology allows us to size up an entire city remotely and work out what the solar potential of the roof space is,” adds Kennedy, who will be speaking at Fortune’s Brainstorm Green conference on Monday. “This is the real secret sauce, the thing that rocks the house.”

Says Joe Kastner, an executive with solar financier MMA (MMA) Renewable Ventures: “If you do a lot of site visits, that can end up being a big portion of the cost. Anything that can make these projects more efficient and cut the costs on the front end is good.” He adds that Sungevity may appeal to potential customers accustomed to managing their lives online and who are loathe to hang out at home waiting for solar sales or service people to show up. “I would be interested in doing as much as possible over the Internet,” Kastner says. “There’s definitely a market for it.”

Rather than employ its own installers, Sungevity will work with unions to train electricians and other contractors so that it can tap pools of green-collar workers in local markets. “That’s probably long-term what’s most needed to achieve a million solar roofs,” says Kennedy, referring to California’s solar target. “[Solar panel] supply is not the big constraint. The real issue is labor — it’s the limiting factor in the growth of the industry.”

At the company’s Berkeley offices down the street from Chez Panisse, Kennedy and Andrew Birch, a board member and solar economics expert, run through a live demo of the Sungevity system. In about 15 minutes, a spokesmodel had walked a potential customer through the sales pitch and ordering process while on the backend a consultant is sizing up the roof with the software tools. Within a day or so an e-mail will be sent to the customer with different solar array options and the relative return on investment. “With a traditional solar installer, that would have been about a two week process,” says Kennedy.

Whether this all works so smoothly once volumes of real-life orders start coming over the transom remains to be seen, of course. And the limits of the system become apparent when Birch types in my Berkeley address and the picture shows a large Japanese maple overhanging my house, which would have ruled out a solar array except the tree had been removed a year and a half earlier. Kennedy acknowledges that leafy cities like Berkeley with its mishmash of architectural styles and every-which-way rooflines are problematic. Instead, Sungevity’s target market is middle-American suburbia, with its vast tracts of cookie-cutter houses.

That’s just fine with potential rival SolarCity, the Foster City, Calif., solar installer backed by PayPal co-founder and Tesla Motors chairman Elon Musk. “Their technology works very well for track homes — that’s maybe 2% of our business,” says SolarCity CEO Lyndon Rive. “Our market is more retrofit homes, existing homes in well-established areas that are looking to go solar.”

“I like it when companies like Sungevity get into the market,” he adds. “They’re forcing innovation and the most important thing is the widespread adoption of solar.”

Sungevity’s launch comes as utilities like Southern California Edison (EIX) and PG&E (PCG) and tech giants like Google (GOOG) are pushing for a mass expansion of solar energy.

Nat Kreamer, president of San Francisco-based solar installer Sun Run, says Sungevity’s move to digitize the solar business is valuable but it will have to focus on the installation process to really get costs down. “Once you figure out how to size up someone’s system, the challenge is the speed you can get it built,” he says.

Installation costs account for roughly half of a solar system’s cost and solar installers like Akeena Solar have developed modular arrays containing wiring and other components to minimize the time spent on installation.

Sungevity will not focus on zeroing out customers’ electricity bills, but like Sun Run, will push the “hybrid home” – selling smaller, cheaper solar systems that will cover that portion of a home’s electricity use that is the most expensive to buy from a utility.

For instance, after rebates, a standardized Sungevity solar array for a four-bedroom home in Northern California will cost about $21,000 and deliver an estimated return on investment of 13% over the system’s 25-year life.

“We’re selling this as an economic asset,” says Kennedy, “not just as a way to go green.”