March 19, 2010 by Todd Woody

photo: Alcoa

In The New York Times on Thursday, I wrote about how aluminum giant Alcoa has become the latest industrial behemoth to jump into the solar business:

Alcoa, the aluminum giant, is testing a new type of solar technology that the company said it believed will lower the cost of renewable energy.

The company has replaced the glass in parabolic troughs with reflective aluminum and integrated the mirror into a single structure.

Parabolic troughs focus sunlight on liquid-filled receivers suspended over the mirrors to create steam that drives an electricity-generating turbine. Parabolic trough technology has been in modern use in solar power plants since the early 1980s, but Alcoa executives said they saw an opportunity to refine the technology and get a foothold in the rapidly expanding renewable energy market.

“If you go out and look behind large parabolic troughs, you’ll find an elaborate truss structure,” said Rick Winter, a technology executive with Alcoa. “From our understanding of aerospace structures, we said if we can modify the wing box design used in aircraft and integrate a parabolic reflector, it would give us a light and stiff structure that would fundamentally affect the cost equation.”

An airplane’s wing box is a unit that integrates support structures and anchors a wing.

“Using aluminum and a wing box design we’re able to create the parabolic curve that we want in the structure itself,” said Scott Kerns, a vice president and general manager at Alcoa. “We can make the skin conform more or less to the way we want to concentrate the light.”

Current solar troughs use glass mirrors that are formed in the shape of a parabola and then attached to a support structure made of aluminum or steel. The executives said they estimate that the all-aluminum Alcoa parabolic trough, which is being tested at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Colorado, will cut the price of a solar field by 20 percent due to lower installation costs.

You can read the rest of the story here.

Posted in alternative energy, solar energy, solar power plants | Tagged Alcoa, parabolic trough, SkyFuel, solar energy, solar power plants, solar trough | 2 Comments »

March 17, 2010 by Todd Woody

Photo: BrightSource Energy

In The New York Times on Wednesday I write that California regulators have recommended approval of BrightSource Energy’s 392-megawatt solar thermal power plant, the first large-scale project in the state in two decades:

California regulators on Wednesday recommended that the state’s first new big solar power plant in nearly two decades be approved after a two-and-half year review of its environmental impact on the Mojave Desert.

The recommendation by the California Energy Commission staff comes three weeks after the United States Department of Energy offered the project’s builder, BrightSource Energy, a $1.37 billion loan guarantee to construct the 392-megawatt Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System, or I.S.E.G.S.

The Sierra Club, Defenders of Wildlife and the Center for Biological Diversity favor solar energy projects but objected to building the BrightSource power plant in Southern California’s Ivanpah Valley, saying it would harm rare plants and animals such as the desert tortoise.

Other environmentalists argued that the project, which features thousands of mirrors that focus the sun on 459-foot-tall towers, would mar the visual beauty of the desert.

In an assessment filed on Tuesday, energy commission staff found that a smaller version of the project that BrightSource proposed last month would mitigate any damage to several protected plant species on the site.

Environmentalists, however, had said the downsized version of the power plant would not sufficiently protect rare species and continued to push for the project’s relocation to more disturbed land.

The energy commission staff determined the visual impact of the Ivanpah power plant could not be reduced but recommended that the commission’s board license the project due to “overriding considerations.”

You can read the rest of the story here.

Posted in alternative energy, BrightSource Energy, solar energy, solar power plants | Tagged BrightSource Energy, California Energy Commission, Ivanpah, solar energy, solar power plants | Leave a Comment »

March 11, 2010 by Todd Woody

photo: Aurora Biofuels

As I write in The New York Times on Friday, it’s spring cleaning at three renewable energy firms as top executives depart SolarReserve, Clipper Windpower and Aurora Biofuels:

The past week has brought a spate of executive departures at renewable energy startups, with the president of SolarReserve, a power plant builder, and the chief executives of Clipper Windpower and Aurora Biofuels stepping down.

Terry Murphy, a rocket scientist who co-founded SolarReserve after a career at United Technologies’ Rocketdyne division, has started a new venture called Advanced Rocket Technologies in Commercial Applications, or ARTiCA. The firm will evaluate green technologies for entrepreneurs and investors, according to Mr. Murphy.

Mr. Murphy and SolarReserve both said the departure was voluntary. “With the company solidly executing on its business strategies, Mr. Murphy has transitioned to an external role in providing developmental expertise to other early stage clean energy companies,” wrote Debra Hotaling, a spokeswoman for SolarReserve, in an e-mail message.

When Mr. Murphy left Rocketdyne to start SolarReserve, the startup licensed Rocketdyne’s molten salt technology so that its solar power plants could store solar energy for use after the sun sets or on cloudy days.

“SolarReserve, in my opinion, is up and running on all four cylinders,” said Mr. Murphy.

“What I did at Rocketdyne and what I did at SolarReserve and what I’m looking at doing in the future is to sift through technologies to find those that can be commercialized.”

Mr. Murphy’s new firm will focus on technologies involving renewable energy, desalinization and sustainability, he said.

You can read the rest of the story here.

Posted in alternative energy, biofuels, Clipper Windpower, enviro startups, environment, renewable energy, solar energy, solar power plants, SolarReserve, wind power | Tagged Aurora Biofuels, Clipper Windpower, Douglas Pertz, Robert Walsh, SolarReserve, Terry Murphy | Leave a Comment »

March 10, 2010 by Todd Woody

photo: Todd Woody

In The New York Times on Wednesday, I write about California regulators’ preliminary decision to reject requests by two big utilities to install grid-connected fuel cells:

While Google, Wal-Mart and other corporations have embraced fuel cells, California regulators have turned down requests from the state’s two biggest utilities to install the technology.

In a preliminary decision, an administrative law judge with the California Public Utilities Commission found unwarranted an application from Pacific Gas and Electric and Southern California to spend more than $43 million to install fuel cells that would generate six megawatts of electricity.

The technology transforms hydrogen, natural gas or other fuels into electricity through an electrochemical process, emitting fewer or no pollutants, depending on the type of fuel used.

“It is unreasonable to spend three times the price paid to renewable generation for the proposed Fuel Cell Projects, which are nonrenewable and fueled by natural gas,” wrote the administrative law judge, Dorothy J. Duda, in a proposed ruling issued last week. “In addition, the applications do not satisfactorily address how full ratepayer funding of utility-owned fuel cell generation would enhance private market investment and market transformation of the fuel cell industry.”

You can read the rest of the story here.

Posted in alternative energy, Bloom Energy, energy, environment, fuel cells, green policy, PG&E, Southern California Edison | Tagged Bloom Energy, California Public Utilities Commission, fuel cells, PG&E, Southern California Edison | Leave a Comment »

March 10, 2010 by Todd Woody

photo: IBM

In The New York Times on Tuesday, I wrote about how scientists at IBM and Stanford University have developed a new process for making plastic that could have major environmental implications:

Researchers at I.B.M. and Stanford University said Tuesday that they have discovered a new way to make plastics that can be continuously recycled or developed for novel uses in health care and microelectronics.

In a paper published in Macromolecules, a journal of the American Chemical Society, the California researchers describe how they substituted organic catalysts for the metal oxide or metal hydroxide catalysts most often used to make the polymers that form plastics.

Chandrasekhar Narayan, who leads I.B.M.’s science and technology team at its Almaden Research Center in San Jose, Calif., said the presence of metal catalysts in plastics means that they often can only be recycled once before ending up in a landfill.

“When you try to take a product and recycle it, the metal in the polymer continues to degrade the polymer so it gets increasingly less strong,” said Mr. Narayan. “If you use organic reactants, you can make certain types of new polymers that are quite different and have other properties plastics don’t have.”

That could give new life to the 13 billion plastic bottles that are thrown away each year in the United States.

“Plastic bottles can be converted to higher value plastics like body panels for cars,” said Mr. Narayan.

Organic catalysts could create a new class of biodegradable plastics to replace those that are difficult to recycle, such as polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, used in a variety of consumer products, including plastic beverage bottles.

You can read the rest of the story here.

Posted in corporate green, environment, green tech, IBM | Tagged IBM, plastics, recyclable, Stanford University | Leave a Comment »

March 8, 2010 by Todd Woody

In The New York Times on Monday, I write about IBM’s new smart grid lab in Beijing that will develop technology for the global market:

In The New York Times on Monday, I write about IBM’s new smart grid lab in Beijing that will develop technology for the global market:

In another sign of China’s emergence as an epicenter of green technology, I.B.M. has opened a lab in Beijing to develop smart grid software for the global market.

“We’re developing solutions for around the world but we’re looking to China to see how the pieces integrate across the value chain,” said Brad Gammons, I.B.M.’s vice president for sales and distribution for the company’s Energy and Utilities division.

Mr. Gammons himself has relocated to Beijing, where he will continue to oversee worldwide sales for the unit.

“The company made a decision that China is a very, very important growth market and to put some executives here,” he said in a telephone interview from Beijing. He said I.B.M. expects the new Energy & Utilities Solutions Lab to drive $400 million in revenue over the next four years.

It is operating out of I.B.M.’s 5,000-person China Development Laboratory. The new lab is working with the State Grid Corporation of China on pilot projects to integrate wind and solar power with the grid, manage grid operations and increase the efficiency of nuclear power plants.

The Chinese government has budgeted $7.3 billion for smart grid-related energy projects this year, according to ZPryme Research & Consulting, a firm based in Austin, Tex.

Mr. Gammons said electric cars will be one focus of I.B.M.’s new lab.

You can read the rest of the story here.

Posted in alternative energy, corporate green, electric cars, energy, environment, green grid, IBM, smart grid, solar energy, wind power | Tagged Beijing, Brad Gammons, China, Energy & Utilities Solutions Lab, IBM | Leave a Comment »

March 8, 2010 by Todd Woody

In my new Green State column on Grist, I write about how an environmental justice group in Texas is using a greenhouse gas analyzer from Silicon Valley’s Picarro to detect pollution from natural gas fracking operations in two communities near Dallas:

If you had been driving through North Texas this week you might have seen a white Dodge Sprinter van circling some of the natural gas wells and compression stations that have sprung up around the Barnett Shale belt like boom-time subdivisions.

Drillers tap natural gas by splitting shale through a process called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, that injects fluids laced with chemicals into the rock formations. The proliferation of shale gas drilling northeast of Dallas has ignited an uproar among residents, some of whom fear that fracking could be poisoning ground water and polluting the air with carcinogens. But the industry won’t disclose all the chemicals it uses and Texas environmental authorities won’t compel them to do so.

Which brings us back to our mystery van. Inside was a desktop computer-sized analyzer connected to a translucent tube that snaked out the roof of the van. The analyzer is made by a Silicon Valley company called Picarro and it provides real-time measurements of methane and other greenhouse gas emissions. By correlating the data with wind patterns, Picarro scientists can pinpoint the source of emissions. Oil and gas operations emit methane, which can also indicate the presence of benzene and other carcinogens, according to Picarro scientists.

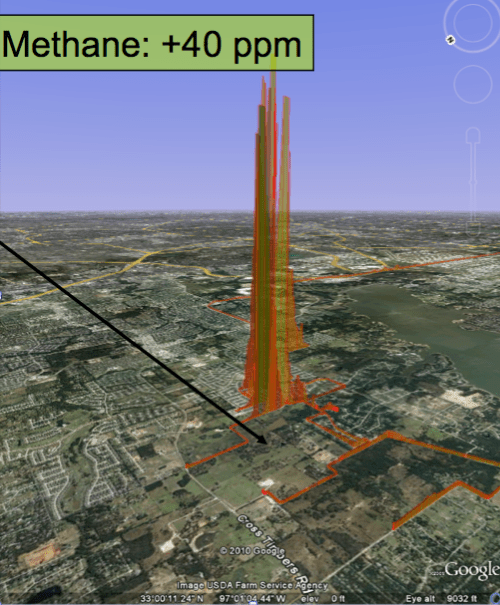

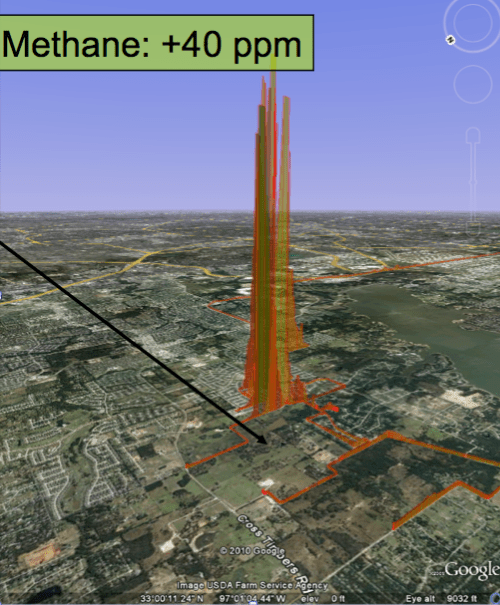

This is an image created by a mashup of the methane concentrations recorded by the Picarro analyzer in Flower Mound, Texas, overlaid on a Google map.

A Picarro employee had driven the van to Texas from California at the request of Wilma Subra, a Louisiana scientist, environmental justice activist and MacArthur genius grant recipient. Picarro’s director of research and development, Chris Rella, flew to Texas and joined Subra and activists from Earthworks’ Texas Oil & Gas Accountability Project on the hunt for fugitive emissions in the towns of DISH and Flower Mound.

DISH — the name is capitalized because in 2005 the town changed its name in exchange for free satellite television from the DISH Network — is home to about 200 people and a dozen compression stations that push natural gas from wells into pipelines. As the Picarro van drove around DISH, concentrations of methane spiked from background concentrations of 1.8 parts per million to 20 parts per million near the compression stations. As the analyzer recorded the spikes they were automatically plotted on a Google map.

Twenty miles to the southeast in the Dallas exurb of Flower Mound, methane concentrations near natural gas wells literally went off the analyzer’s chart, topping 40 parts per million, says Subra and Picarro executives.

“I see this as very, very beneficial to the environmental justice movement,” says Subra. “It gives you real-time data and you can potentially identify the source as opposed to having to collect air samples and then have them analyzed. You can see the plume on the map and how close houses are to the compressor stations.”

You can read the rest of the column here.

Posted in climate change, global warming, green tech, Picarro | Tagged DISH, Earthworks, Flower Mound, fracking, Picarro | 2 Comments »

March 8, 2010 by Todd Woody

In The New York Times last week, I wrote about how Yingli, the Chinese solar module maker, is heading east after capturing nearly a third of the California market last year:

In The New York Times last week, I wrote about how Yingli, the Chinese solar module maker, is heading east after capturing nearly a third of the California market last year:

Yingli, the Chinese solar module maker that captured nearly a third of the California market last year, has struck a deal to supply a New Jersey developer with more than 10 megawatts of photovoltaic panels.

The agreement announced Tuesday with SunDurance Energy for the first time brings Yingli’s reach to the East Coast. SunDurance, owned by a construction and engineering firm, the Conti Group, will install the Yingli solar panels on rooftops, in carports and in ground-mounted solar farms.

“Being able to have a presence on both coasts and in some of the other states that are emerging is very significant for us,” Robert Petrina, the managing director for Yingli’s American operations, said.

He said Yingli shipped 15 megawatts of modules in the fourth quarter of 2009 in the United States. The deal with SunDurance calls for Yingli to provide 10 megawatts through the third quarter of this year. The company had previously supplied solar panels to SunDurance for other projects.

Yingli, based 100 miles south of Beijing in the city of Baoding, opened offices in New York and San Francisco at the beginning of 2009. By year’s end, the company held 27 percent of the California market, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, a research and consulting firm. Its stock is listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

Chinese firms, including the Yingli rival Suntech, increased their share of the California market to 46 percent, up from 21 percent at the beginning of 2009.

Mr. Petrina said declines in the price of polysilicon — a vital ingredient in solar cells — and in subsidies paid by European countries made it feasible for Yingli to enter the American market.

You can read the rest of the story here.

Posted in alternative energy, solar energy, Suntech, Yingli | Tagged China, solar industry, solar panels, Suntech, Yingli | Leave a Comment »

March 8, 2010 by Todd Woody

photo: Todd Woody

photo: Todd Woody

In an interview I did with green tech entrepreneur Bill Gross for Yale Environment 360, Gross talks about the future of solar energy, his relationship with Google, and how to avoid battles over building large solar farms in the deserts of the Southwest:

Bill Gross is not your typical solar energy entrepreneur. In a business dominated by Silicon Valley technologists and veterans of the fossil fuel industry, Gross is a Southern Californian who made his name in software. His Idealab startup incubator led to the creation of companies such as eToys, CitySearch, and GoTo.com. The latter pioneered search advertising — think Google — and was acquired by Yahoo for $1.6 billion in 2003.

That payday has allowed Gross to pursue his green dreams. (As a teenager, he started a company to sell plans for a parabolic solar dish he had designed.) Over the past decade, Gross has launched a slew of green tech startups, including solar power plant builder eSolar, electric car company Aptera, and Energy Innovations, which is developing advanced photovoltaic technology.

But it has been eSolar, backed by Google and other investors, that has been Idealab’s brightest light. In January, the company signed one of the world’s largest green-energy deals when it agreed to provide the technology to build solar farms in China that would generate 2,000 megawatts of electricity — at peak output the equivalent of two large nuclear power plants. And last week, eSolar licensed its technology to German industrial giant Ferrostaal to build solar power plants in Europe, the Middle East, and South Africa. Those deals followed eSolar partnerships in India and the U.S.

ESolar’s power plants deploy thousands of mirrors called heliostats to focus the sun’s rays on a water-filled boiler that sits atop a slender tower. The heat creates steam that drives an electricity-generating turbine. Last year, eSolar built its first project, a five-megawatt demonstration power plant, called Sierra, in the desert near Los Angeles.

This “power tower” technology is not new, but what sets the company apart is Gross’ use of sophisticated software and imaging technology to control the 176,000 mirrors that form a standard, 46-megawatt eSolar power plant. That computing firepower precisely positions the mirrors to create a virtual parabola that focuses the sun on the tower. That allows the company to place small, inexpensive mirrors close together, which dramatically reduces the land needed for the power plant and cuts manufacturing and installation costs.

“We use Moore’s law rather than more steel,” Gross likes to quip, referring to Intel co-founder Gordon Moore’s maxim that computing power doubles every two years.

You can read the interview here.

Posted in alternative energy, energy, enviro capitalism, enviro startups, environment, eSolar, Google, green startups, green tech, solar energy, solar power plants | Tagged Bill Gross, eSolar, green technology, solar energy, solar power plants | 2 Comments »

February 26, 2010 by Todd Woody

photo: Todd Woody

In my latest Green State column in Grist, I take a look at why, despite the hype, Bloom Energy’s fuel cell breakthrough could change the energy game:

Green tech had its Google moment this week in Silicon Valley when one of the most secretive and well-funded startups around, Bloom Energy, literally lifted the curtain on what it claims is a breakthrough in fuel cell technology: affordable electricity! Fewer greenhouse gas emissions! And that’s all before they throw in the bamboo steamer.

After eight years in stealth mode—until this week, Bloom’s website featured the company’s name and little else—the startup pulled out the stops in a carefully stage-managed media blitz that recalled the high-flying dot-com days of a decade ago. First came a report on “60 Minutes” that got the blogs abuzz along with stories in Fortune and The New York Times.

It all culminated in a star-studded press conference at eBay’s headquarters in San Jose on Wednesday, where California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger introduced Bloom’s co-founder and chief executive, K.R. Sridhar, and gave him a bear hug before several hundred suits, environmental movement honchos and a bank of television cameras.

Before Colin Powell, the former secretary of state and a Bloom board member, delivered the benediction, testimonials were offered by Google co-founder Larry Page and top executives from Wal-Mart, eBay, Federal Express, Coca-Cola, and other Fortune 500 companies that had quietly purchased 100-kilowatt Bloom Energy Servers over the past year.

New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), meanwhile, beamed in a bipartisan endorsement via video.

“This technology is going to fundamentally change the world,” the California Democrat declared.

But is it?

That’s the $400 million question (what some of Silicon Valley’s most storied venture capitalists have poured into Bloom so far).

With the hype—the apparently brilliant but unassuming Sridhar was compared to Steve Jobs at one point Wednesday—comes the backlash. Almost immediately analysts and competitors began asking hard questions about Bloom’s claims.

And there are some big unknowns. Will the fuel cell stacks last as long as the company anticipates or will frequent replacement undermine the economics of going off the grid, for both Bloom and their customers?

What’s the total cost of ownership for customers? Bloom says the energy servers have a lifespan of 10 years and a payback period of three to five years. That’s based on the current price of natural gas—which is one fuel used by the devices—and state and federal subsidies that halve the cost of the machines that sell for between $700,000 and $800,000. Will Bloom be able to scale up manufacturing and continue to innovate to bring the price of the energy server down? Can they be competitive without subsidies?

All legitimate questions. But it’s important not to lose sight of what looks to be some fundamental breakthroughs, not only in energy technology but in the way some major corporate players are embracing distributed generation-placing electricity production where it is consumed.

You can read the rest of the column here.

Posted in Bloom Energy, energy, fuel cells, Google | Tagged Bloom Energy, fuel cells, Google, K.R. Sridhar, Wal-Mart | 1 Comment »

« Newer Posts - Older Posts »