For those readers who missed Green Wombat’s feature story on the solar land rush in the July 21 issue of Fortune – available here at Fortune.com – I reprint below.

The Southwest desert’s real estate boom

From California to Arizona, demand for sites for solar power projects has ignited a land grab.

By Todd Woody, senior editor

(Fortune Magazine) — Doug Buchanan grins with relief when he sees the carcasses. He has just driven up a steep dirt road onto a vast, sunbaked mesa overlooking the Mojave Desert in western Nevada. There, a few feet from the trail, lie the corpses of two steers. A raven perches on one, the only object more than three feet above the ground on this pancake-flat plateau. Cattle, dead or alive, qualify as good news in Buchanan’s line of work. If cattle are present, that means grazing is permitted, and that in turn means that this land is most likely not protected habitat for the desert tortoise.

Buchanan, 53, is scouting sites for a solar power company called BrightSource Energy, an Oakland-based startup backed by Google and Morgan Stanley. The blunt, fifth-generation Californian, who used to survey the same area for natural-gas power sites, knows that the presence of an endangered species such as the tortoise could derail BrightSource’s plans to build a multibillion-dollar solar energy plant on the mesa.

BrightSource badly wants these 20 square miles of federal land on what is called Mormon Mesa. The company was in such a hurry to stake its claim with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management that it applied for a lease sight unseen. That’s an expensive gamble for a startup, given that application fees alone run in the six figures. “I usually like to go out and kick the tires before filing a claim,” Buchanan says, “but there’s a lot of competitive pressure these days to move fast.”

That’s putting it mildly. A solar land rush is rolling across the desert Southwest. Goldman Sachs, utilities PG&E and FPL, Silicon Valley startups, Israeli and German solar firms, Chevron, speculators – all are scrambling to lock up hundreds of thousands of acres of long-worthless land now coveted as sites for solar power plants.

The race has barely begun – finished plants are years away – but it’s blazing fastest in the Mojave, where the federal government controls immense stretches of some of the world’s best solar real estate right next to the nation’s biggest electricity markets. Just 20 months ago only five applications for solar sites had been filed with the BLM in the California Mojave. Today 104 claims have been received for nearly a million acres of land, representing a theoretical 60 gigawatts of electricity. (The entire state of California currently consumes 33 gigawatts annually.)

It’s not just a federal-land grab either. Buyers are also vying for private property. Some are paying upwards of $10,000 an acre for desert dirt that a few years ago would have sold for $500.

No doubt the prospect of potential riches is overheating expectations. But California and surrounding states have mandated massive increases in renewable energy in the next few years. That has led some experts at Emerging Energy Research of Cambridge, Mass., to predict that Big Solar could be a $45 billion market by 2020.

Meanwhile, the land rush is setting the stage for a showdown between solar investors and those who want to protect a fragile environment that is home to the desert tortoise and other rare critters. The Southwest is on the cusp of what could be a green revolution. And the biggest obstacle of all may be … environmentalists.

***

Over the past year a parade of executives bearing land claims have made the trek to a stucco BLM office just off the interstate in the dusty city of Needles, Calif., a 110-mile drive south from Las Vegas. (It’s the town where the late “Peanuts” cartoonist, Charles M. Schulz, briefly lived as a boy; in the comic strip, Snoopy’s brother Spike is a resident.) The Bush administration has instructed the BLM to facilitate renewable-energy projects (along with nonrenewable ones). But Sterling White, the BLM’s earnest Needles field manager, is also concerned about what could happen if they transform the Mojave into a collection of giant power stations. “One of our biggest challenges is the cumulative impact of these projects,” he says.

Nearly 80% of the land that White’s office oversees is federally protected wilderness or endangered-species habitat. That leaves about 700,000 acres for solar power plants, only some of which are near transmission lines. Land leases are handed out on a first-come, first-served basis, but White is also supposed to weed out speculators from genuine solar developers based on loose criteria such as who is negotiating with utilities and who is applying for state power licenses. White has yet to approve a single lease, but he has summarily rejected four because they lie in protected-species habitat.

***

Solar prospectors tend to be as secretive about their land as forty-niners were about the veins of gold they discovered. Most bids are placed by limited-liability corporations with opaque names that conceal their ownership. And no one has been as quick to move into the Mojave – or as tightlipped about it – as Solar Investments.

That entity, it turns out, is Goldman Sachs’s solar subsidiary. The investment bank’s designs on the desert are a topic of intense interest and speculation. Goldman declined to comment. But here’s what we know:

Solar Investments filed its first land claim in December 2006 and within a month had applied for more than 125,000 acres for power plants that would produce ten gigawatts of electricity. Many of the sites lie close to the transmission lines that connect the desert to coastal cities. (Goldman has also staked claims on 40,000 acres of the Nevada desert.)

Nobody expects Goldman to begin operating solar plants. It will probably either partner with another developer or sell its limited-liability company (and its leases) outright. The firm has been making the rounds of solar developers. “The conversation’s been pretty wide-ranging, primarily as an investor interested in financing deals,” says one solar energy executive approached by Goldman. “But there’s clearly an element of interest in our technology.” Goldman has requested permission to install meteorological equipment on its sites and is evaluating “competing technologies, including solar dish systems, power towers, and large-scale photovoltaic arrays,” according to a letter Goldman sent to the BLM in August 2007.

Competitors are lining up behind Goldman, staking claims on some of the same sites in hopes the bank will abandon them. PG&E and FPL, for instance, are in the queue after Goldman on one site. Solel, an Israeli solar company that last year scored a contract to deliver 553 megawatts to PG&E, is third in line behind Goldman on another.

“I view Goldman as a very interesting indicator of things to come,” says Brian McDonald, PG&E’s director of renewable-resource development. “They’re usually ahead of the curve – you can extract a huge amount of value if you get in early.” There’s other smart money here too. A Palo Alto startup called Ausra received $40 million from the elite green venture capitalists Vinod Khosla and Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. Ausra has signed a deal with PG&E and announced its intention to construct a gigawatt’s worth of projects a year.

Most of the power production contemplated for the Mojave will rely on solar thermal technology – the common approach in large-scale generation projects – in which arrays of mirrors heat liquids to produce steam that drives electricity-generating turbines. But a secretive Hayward, Calif., startup called OptiSolar has filed claims on 105,300 acres to build nine gigawatts’ worth of photovoltaic power plants, which employ solar panels similar to those found on residential rooftops. (The company also has applied for leases on 21,800 acres in Arizona and Nevada.) To put those ambitions in context, the biggest photovoltaic power plant operating today produces 15 megawatts. Says OptiSolar executive vice president Phil Rettger: “We have a proprietary technology and a business approach that we’re convinced will let us deploy PV at large scale and be competitive with other forms of renewable energy.”

***

With the prime BLM sites quickly being snapped up – recently the agency temporarily stopped accepting new land claims while it develops a desertwide solar policy – competition is growing for private land. Here, too, the emphasis on secrecy borders on the obsessive. A request to view a piece of desert that is up for sale is treated as if I had asked to visit Area 51.

Waiting outside a roadside diner in southwestern Arizona – I’ve promised not to say where – with BrightSource senior vice president Tom Doyle, I expect to see a weather-beaten farmer come chugging up in a battered pickup. Instead, a pale-green Volvo SUV driven by a physician glides into the parking lot. The doctor, who wishes to remain anonymous, acquired the land two years ago as the renewable-energy boom got underway. “We thought we’d put solar on it – that’s the reason we bought it,” the doctor says as we pile into the Volvo and head into the desert to visit the site. After about five miles we turn off the road and come to a stop in a rocky patch of desert framed by low-slung mountains and buttes. Doyle quizzes the physician about water rights, endangered species, and access to transmission lines before moving out of earshot to talk dollars. The whole process takes only about 20 minutes – the two sides ultimately decide not to do a deal – and then Doyle is on to visit the next potential property.

Such is the land frenzy that farmers in Arizona were paid $45 million for 1,920 acres by Spanish solar company Abengoa so that it could build a 280-megawatt power plant; the land had an assessed value of a few hundred thousand dollars. The company also plunked down $30 million for 3,000 acres in the California Mojave that had traded hands for $1.25 million nine years earlier. That prompted developer Scott Martin to put his adjacent 300-acre parcel – land he had bought only a few months earlier for $457,500 – on the market for $3 million. Also for sale: a $15 million, 3,000-acre tract near Palm Springs, which Martin began shopping around to solar executives like Ausra’s Perry Fontana. When I join Fontana to check out the site, a onetime World War II air base outside the Mojave ghost town of Rice, he says, “I probably get three calls a day from brokers or landowners.” As if on cue, his Bluetooth earpiece lights up with a cold call from a broker peddling some land near Needles.

***

Green energy is not about to get a green light from all environmentalists. “We’re going to challenge these big solar projects, and there’s going to be tremendous environmental battles,” says veteran California activist Phil Klasky, a member of several green groups who helped lead a campaign in the 1990s that scuttled a radioactive-waste dump planned in tortoise territory in the Mojave. “Large solar arrays will have an impact on surrounding critical habitat for the desert tortoise and other threatened species. We have to fight global warming, but just because it’s solar doesn’t make it right.”

The developers are worried about resistance. “I remember the spotted owl,” says Fred Morse, a former Department of Energy official who is a senior advisor to Abengoa’s U.S. operations. The widespread logging of ancient forests, home to the northern spotted owl, set off epic environmental fights in the 1980s and ’90s. As Morse puts it, “The Mohave ground squirrel or the desert tortoise – any one of them could become a cause.”

Solar energy companies may make for less tempting targets than timber barons, but development of the desert has never been attempted on such a scale. The result is that some environmentalists find themselves anguished over which side to take. “We’ve had our share of conflicts over endangered species in this state, no doubt about it,” says Kevin Hunting, a biologist and a deputy director of the California Department of Fish and Game, which enforces the state endangered-species laws. “We’re actively looking to strike that critical balance between the state’s renewable-energy goals and conserving species that are vulnerable. It’s challenging.”

California wildlife regulators, for instance, have peppered Ausra with requests for more biological surveys on the site of a 177-megawatt solar power plant to be built in San Luis Obispo County. The feds could also require Ausra to prepare a plan to protect the San Joaquin kit fox, a process that could take years and shred the project’s economic viability.

Worse for developers, state and federal law require wildlife officials to consider the total impact of multiple projects when weighing whether to approve any individual facility. Next door to Ausra’s solar farm, for example, is OptiSolar’s planned 550-megawatt power plant, which would cover 9 1/2 square miles of potential endangered-species habitat with solar panels. Will the regulators approve one? Both? Nobody knows.

In the meantime, the solar land rush is unlikely to cool down. Which is why Morse wants to keep quiet Abengoa’s $30 million real estate deal. The company is applying to build a 250-megawatt solar power plant on the site, and it may be in the market for more land. “We don’t want to publicize that purchase,” he says, “as the speculators will be coming out of the woodwork.”

Read Full Post »

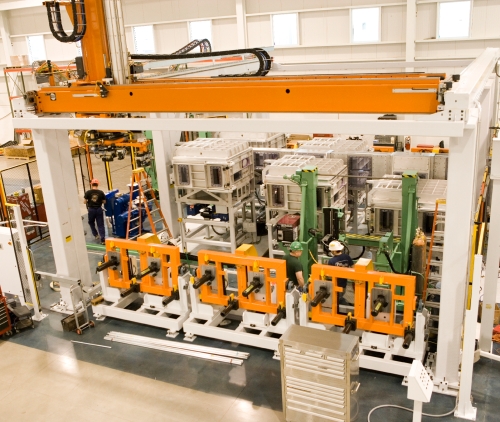

“Our processes really require high productivity, so what makes it competitive here in the Midwest is that we have a great labor force that is eager to work and well-trained already,” ECD chief executive Mark Morelli told Green Wombat on Monday.

“Our processes really require high productivity, so what makes it competitive here in the Midwest is that we have a great labor force that is eager to work and well-trained already,” ECD chief executive Mark Morelli told Green Wombat on Monday.